Whether it is at the service of rich traders, people looking for raw materials in mines or a private citizen eager to give a present to his beloved… we should get over it: today gemmology is a scientific discipline to all intents and purposes. Developed as a branch of mineralogy, emerged among the ordered framework of crystallography, divorced from applied mineralogy due to its uniqueness, gemmology bloomed as a first rank science also in laboratories and in the classrooms of the most important universities in the world. We are at the point that gemmology occupies many lines of research, both academic and private, and a number of investments are made to study gems under any point of view in order to discover whether they are natural, treated or what kind of treatment they have undergone, if any. Mineralogy studies minerals, meteoritics studies meteors, palaeontology studies fossils while gemmology studies gems. When an expert of meteoritics is asked “what is a meteor?” he will promptly answer: “a rocky object, of extraterrestrial provenance, touching the earth surface after going through its atmosphere”. For every scientific discipline I obtain similar answers to the question made on the object of the study. However, what happens if I ask a gemmologist: “what is a gem?”

www.thebeautyintherocks.com

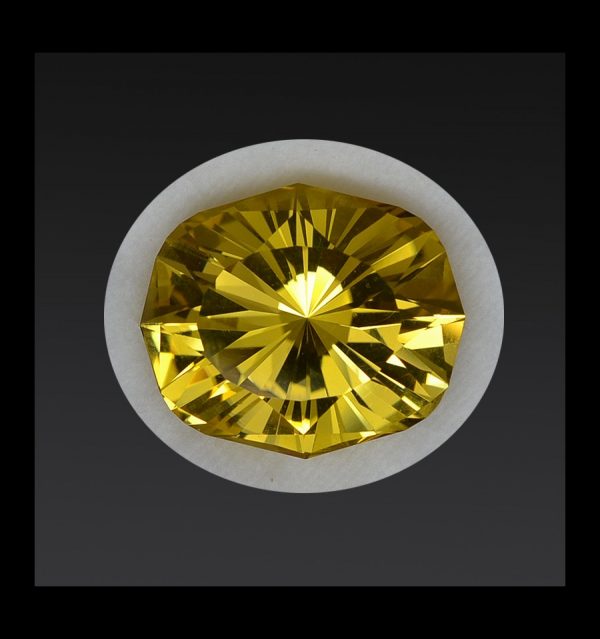

I met internationally renowned gemmologists who promptly made a list of all the possible inclusions in quartzes, the types of treatments existing on corundum, or all the micro differences between opals coming from various mines. However, no “gemmostar” has ever confidently and easily answered this simple question: “what is a gem?”. Some told me that a gem is “a mineral or other material that once cut and polished can be used in jewellery”. But look at the barytes in Figure 1, it is a mineral you can alter just touching it with your sweaty hand. It is scratched with a nail and would be the last thing to be used in jewellery! Would you dare say that it is not a gem? On the contrary, in my opinion it is one of the most extraordinary gems I have ever seen. I could go on with a list including outstanding gems of calcite, scheelite, phosgenite, cerussite and plenty of other minerals that can be turned into marvellous gems, even without being necessarily set within uncomfortable and dangerous golden traps. Other gemmologists told me that a gem is “a precious or semi precious stone that once cut and polished can be used as a gem”. I swear that some use exactly this definition!!! That is, a gem is a stone that can be used as a gem!!! (Figure 2) It is as if I asked “what is a car?” and they would answer me: “some pieces of metal and other materials that are assembled to create a car!”. I turned to Wikipedia and I found out that, according to them, a gem is “a crystal of mineral that once cut and polished can be used in jewellery”. So we are going back to the previous issue, getting it even worse as this definition does not include rocks (like lapis lazuli) or organic materials (pearls, etc.).

Then, let us continue with another designation I was given: “a mineral that for its beauty, durability and rarity is suitable to be cut as a gem”. Here I really started to get discouraged. So is it true that a gem is a mineral that is cut to become a gem? Am I the only one who does not bait to such gibberish and is not able to understand what a gem is? As when they ask you: “How was life born on our Planet?” and they answer “a meteorite brought it from another planet…” Well, that is right, but how was the first life form born there? Then, coming back to our gems, why should the mineral be rare in order to be regarded as a gem? Amethysts are very common, maybe they are cheap, but is this a reason for not considering them as gems? (Figure 3)

After dozens of other similar definitions, I really appreciated the answer given by the International Gem Society that to the question “what is a gem?” simply replies: “I feel sorry… since simply no concise definition covers all the materials that have been regarded as gemstones throughout the centuries”. Finally something concrete to work on!!! Reality is that no acceptable definition of gem including all cases and being truly exhaustive can be given. However, I have been a gemmologist all my life and the fact that no definition exists for the thing I love the most, has always really driven me nuts! So I started looking for a definition proceeding step by step, putting pen to paper the standing points of a gem, a marvellous and indefinable wonder of nature forged by man. The first is the starting material of a gem, something nature produces and that we can easily describe with surgical scientific precision. We should only make right decisions able to include all possibilities, as we can obtain a gem from a mineral but also from a rock and organic material! The second equally significant point is that gems are not produced in nature, but they inevitably need the work of man. And man works to earn. This leads to another important consideration, as in the definition of gem we can not rule out the link with the trade world. The third point implies that a gem is beautiful, though beauty is something that cannot be expressed in scientific terms; what is beautiful for me maybe it is not for another person. I saw cabochon made of fossil dinosaur excrements (also called coproliths) that some people considered charming. The gem is something that has no use, though it fascinates, costs sacrifices, but gives satisfactions and is usually both the first important gift we receive (baptism, communion, weddings, etc.), and also the last we give (as inheritance after death). For some a gem stands for man’s shallowness, while for others is the symbol of the love of a lifetime. A gem is a tiny thing with a huge value, the triumph of all on nothing and of nothing on all. Maybe this is why we are still unable to define what a gem is! Therefore, over time I have learnt a critical lesson that can help me give a definition of a gem: even if it is impossible to find a strict scientific definition, we should necessarily merge science and poetry, art with trade, practicality with philosophy, otherwise we will never obtain a proper definition! Oscar Wilde said: “if you feel upset as the world seems out of control, my advice is: take a gem! Nothing more than a gem can give you this sense of permanent stability”. I agree with Oscar Wilde who managed to catch the essence of a gem and I like to think that I was inspired by his words in my search for the right definition. Therefore, let us begin the path that will lead to determine what a gem is, considering that a definition must be complete, suitable for any case, irreproachable and, above all, concise. It is true that gemmology derives from mineralogy, but as said before, claiming that a gem is necessarily a mineral being worked is wrong. Is there a word able to combine minerals, corals, rocks and dinosaur excrements? In my gemmological life I have seen cutting any kind of object, but never something in liquid or gaseous state; and then, all the gems I have examined originate from materials that formed due to natural causes; for this reason I think that the definition of a gem should start with “a natural solid body”. I partially agree with what written in other hypotheses, in the part concerning human intervention. No gem exists that is not worked (I saw setting raw crystals and other not worked items, but they can not be considered gems as other terms to define them are already adopted). Writing “cut and polished” seems to me as incorrect, since some gems exist where man just polishes without faceting or creating a cabochon (I am referring to sections of tourmalines, trapiche emeralds, corundums, etc.) Therefore, I would write “altered by a living being”. Why haven’t I written “man”? Because I consider a pearl as a gem (diamonds, coloured stones and pearls are taught in any gemmology class) and a pearl is nothing less than a “natural solid body” (e.g. a grain of sand), “altered” by a living being (either bivalve or gastropod) without any human intervention in its working. (Figure 4)

We should then determine “when” a gem is created. What really drives a cutter to create a gem? The cutter starts working if someone buys what he produces. It doesn’t matter if the starting material is rare, durable, beautiful, transparent, opaque, precious or semiprecious, or if it will be set in a jewel or put in a collection case. If someone is ready to pay for the working of a material, then that gem will be created. For this reason I would add ”marketed” to my definition. Such term implies that someone associates the concept of beauty to the gem. Since it is not a primary good, only an aesthetic value allows for the sale of the object. If someone buys a gem it means that he has found it beautiful and is ready to invest money to purchase it. Someone could object that despite its beauty, a gem could be also bought for mere economic reasons. Very true! Therefore, the term “marketed” present in this definition of gem is, by this, further strengthened. We are only left to understand the use of a gem. I only partially agree with those writing “to be used in jewellery” as, actually, many gems are part of private collections and will never be set. Then, I would write “with the possibility of being used in jewellery”. At this point I try to put all these elements together to see what I have obtained! What is a gem? A gem is “a natural solid body altered by a living being and marketed with the possibility of being used in jewellery”. Is the definition right? I think so. Can it be improved? Maybe. What I can say is that all the definitions I have come across so far were wrong and/or incomplete, while this fully satisfies my gemmological soul. Yet, someone could object: “and if I cut a piece of glass, or a synthetic ruby? aren’t they gems? The answer is simple: In my opinion they are not gems, as they should be more correctly described as “gemmological material”, whose definition would be merely “a natural or artificial solid body altered by a living being and marketed with the possibility of being used in jewellery”. (Figure 5)

Please, leave a simple dreamy gemmologist with the idea that the sophisticated products of an aseptic industrial chemical laboratory find no place in the definition of a gem. I hope this definition can be satisfactory for you as it was for me. If, instead, it still leaves you upset, this is my advice: take a gem! Nothing more than a gem can give you this sense of permanent stability…

Request your copy of Rivista Italiana di Gemmologia or buy a yearly subscription

Article by Michele Macrì, published on Rivista Italiana di Gemmologia #1, May 2017.