This is not the first time that gemologists rummage through the mysterious spaces of crystals and end up being so surprised by the images they produce, that they ask themselves whether they have stepped into another area: the field of real art. When, after printing them, these photos become tangible objects like paintings, their question becomes clearer: is there a spontaneous form of art that doesn’t need human beings any more, revealed by the simple reproduction of innate phenomena? After all Pliny himself, a precursor of all “modern” gemological reasoning, warned scholars to consider gemstones precious just because they have the priceless value of making us contemplate the spectacular and intriguing lessons to learn from Nature. According to the great Latin naturalist, their beauty contained an explicit invitation to contemplation. An invitation for us, miserable and frail humans, to immerse and lose ourselves in them and read the wonderful design of the perfect system of the Magister Vitae, which gave order to the world.

We know what happened then. In more recent times, figurative arts got free from the imprisonment of a faithful, essential, monotonously unavoidable representation of nature. Artists engaged in frantic attempts at abstract forms, geometric reversals, changes of perspective. The last one hundred years of great painting have offered us a new aesthetic approach that has trained our eyes to eccentric shapes and colours, far from the classical representations of art.

Here’s a question though. Should we adapt to Nature, by imitating it, just as Pliny suggested? Or are the gemological images of inclusions works of art accomplished by nature, which anticipates our creative inspirations? After enlarging them thirty and more times, don’t we recognise, in certain arrangements of the materials imprisoned within the crystals, the same abstract signs of an artist like Pollock? The comparison seems legitimate. Traces of colour flutter in those paintings just like the fluids captured by gems. The comparison is obvious, and it could be discussed.

In this inspiring field, some of the many interesting photos taken by Willi Andergassen, an avid Italian stone expert and former aviator who died in 2001, were reproduced on canvas and shown to the public about ten years ago. The curators of the exhibitions with Andergassen’s photos fully captured the great potential of the images he had managed to capture in the hidden world of crystals. And all this was done in an era when filming and development techniques were still far from the endless possibilities of modern digital technology.

These, which are obviously trigons in a diamond, evoke a mysterious carpet of perfect triangles. The composition obtained from the beautiful cut of a photograph suggests a creation that emphasises geometric symbols, a bit like Piet Mondrian’s essential squares. And doesn’t Mondrian himself, in the composition below, evoke the coplanar, iso-oriented pattern of many tubular or needle-like inclusions found in many gemstones?

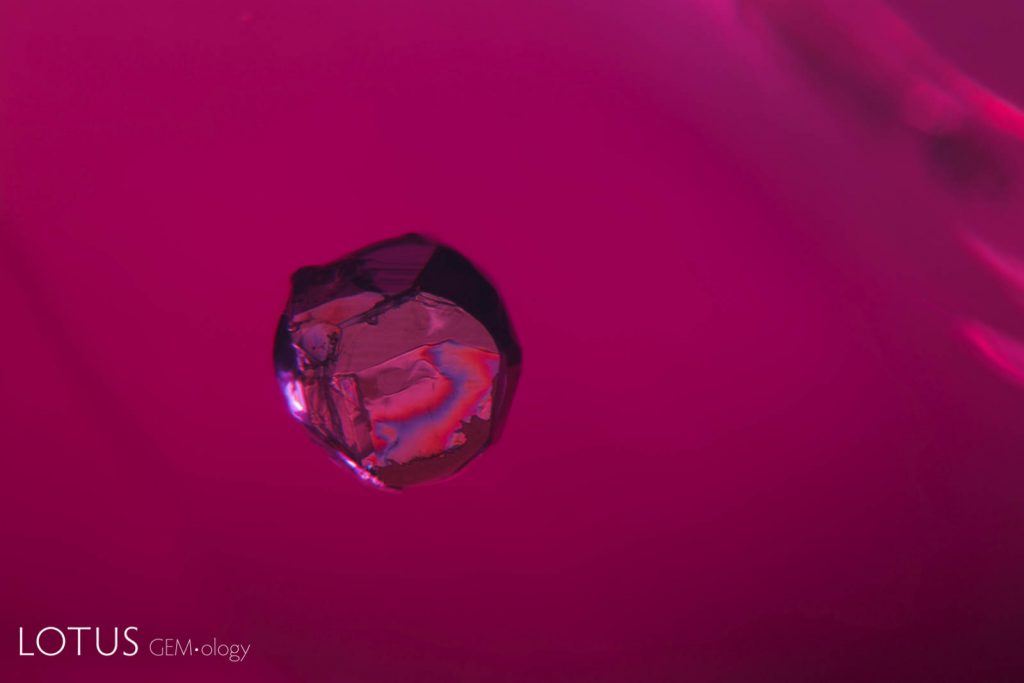

In more recent times, in November 2017, the theme of close-up photography of gemstones was relaunched in China by the Tongji Zhejiang College in collaboration with Lotus Gemology, the Shanghai Bairui Jewelry Corporation. Those who know Lotus Gemology also know that it’s basically the Hughes family. Dick Hughes is one of the most eclectic gemologists worldwide. His approach is very peculiar and intriguing. When I met him at Ciges in Naples, I was impressed by his method, which is intended to include the emotional aspects of knowledge. His presentation aimed at delivering this vibrant sense of the search for beauty. It’s no coincidence that I described it as a form of Humanistic Gemology and, not surprisingly, in China, Dick’s talented daughter Billie showed some of her pictures of inclusions together with images from the places where they had been produced, a long, magnificent reportage that tells the story, the journey and the life of gemstones.

Billie’s photos have a sharp, ruthless definition that evokes the multidimensional focus of today’s most successful digital animation films. Except that in there it’s all true, and, in addition to deep fascination, these shots have an incredible educational value. To conclude (but we’ll talk about it again soon), I think there’s nothing better than this quote by the philosopher John Armstrong: “The experience of beauty, we may then say, consists in finding a spiritual value (truth, happiness, moral ideals) at home in a material setting (rhythm, line, shape, structure), and in such a way that, when we contemplate the object, the two seem inseparable”.

Paolo Minieri