In an acute phase of decline, will the world economy still want to ask itself if rough diamonds really reach the cutting phase without any bloodstain? Is the Kimberley Process (KP), the most important international responsibility commitment for gemstones supply (see “Box 1 – How does the Kimberley Process work? Diamond rough can be traded only by participant nations”), in crisis? Will it be replaced by other traceability tools, such as the blockchains? Does it still provide guarantees for the supply chain integrity? This complex mechanism of intergovernmental cooperation that implements an import/export certification scheme for rough diamonds (KPCS) shows a series of critical points. Reforms were loudly called for in 2016 during the KP International Meeting, under Australian direction. Skepticism on the actual performance of the scheme has began circulating in the public opinion for some time. This is why members have started a three-year cycle work in an attempt to improve the rough diamonds certification system. This was the last call to put the diamond sourcing legitimacy project back on tracks. It seems that things went wrong. Today time has run out and, with the world turned upside down by COVID-19, ethics must give hasty solutions. KP is increasingly at risk.

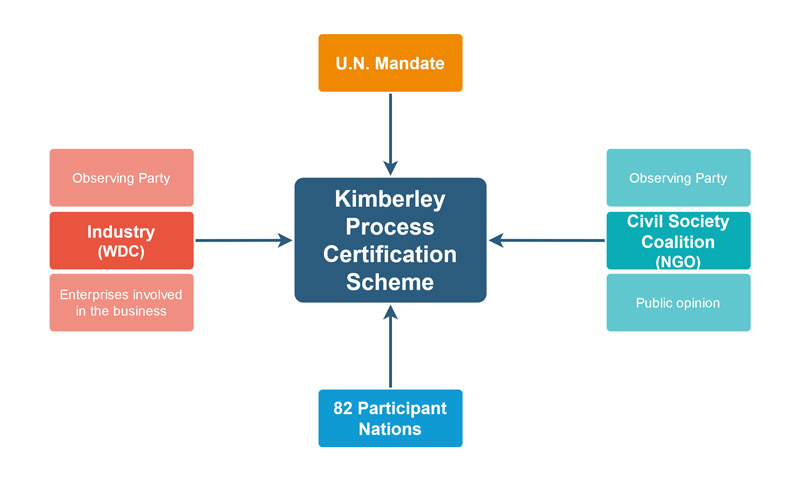

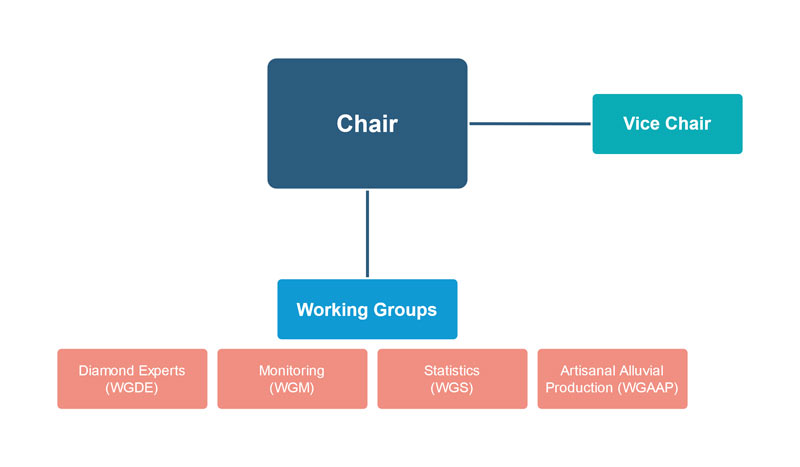

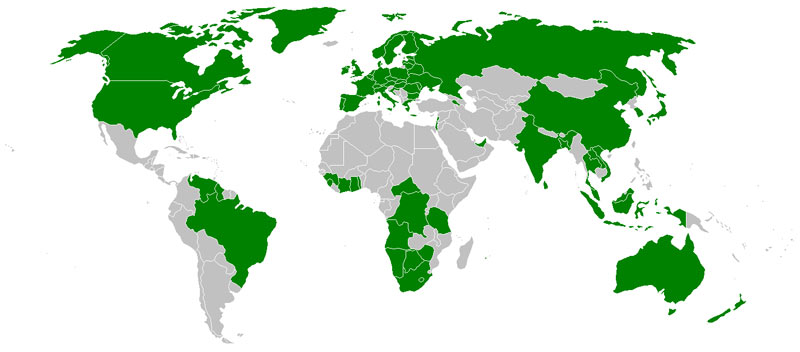

Box 1 – How does the Kimberley Process work? Diamond rough can be traded only by participant nations

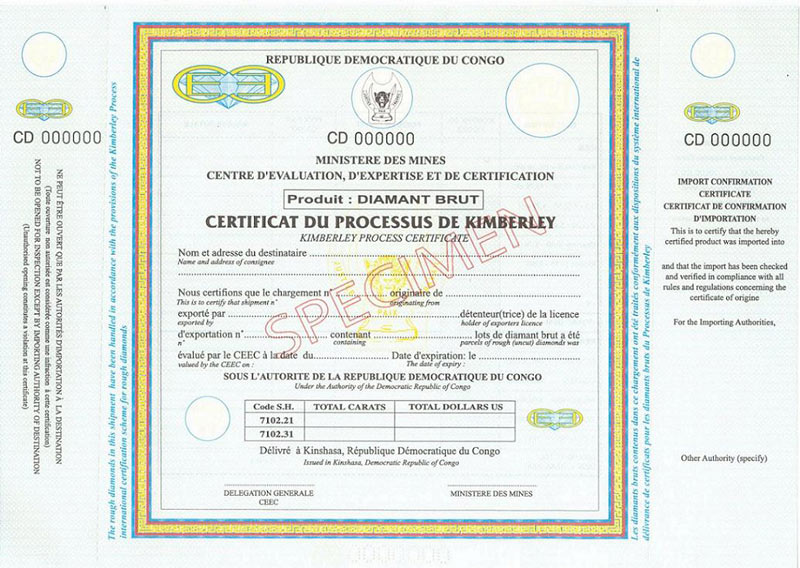

Rough diamond exportation and importation can only take place between participating countries. This is the basic principle inspiring the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme. Appropriate documents, provided by the legitimate authority in the country of origin and consisting of a certificate observing shared minimum regulatory standards must accompany each shipment of rough diamonds at the time of export. Given that the remaining rules of the certificates vary from country, as they are implemented and enforced at the national level, penalties are also imposed by national laws.

The KPCS does not have its own general secretary, budget or personnel. It has a rotating Chair, elected on an annual basis at a plenary meeting, with political as well as administrative duties and assuming most of the costs of the system, with voluntary support provided by the rest of the participants which shall report to the Chair about their practices and the domestic implementation of the KPSC. So far, South Africa, Canada, Russia, Botswana, the European Union, India, Namibia, Israel, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the United States of America, South Africa, the Republic of China, Angola, UAE, Australia and India have been in charge.

Are abuses occurring only in presence of civil wars? If not, in Delhi the opportunity of reforming the KP was lost

The moment of truth has finally arrived. Three years have passed and today inexorably all the weaknesses emerged. The appointment was scheduled in New Delhi in November 2019 for the KP Plenary Meeting. As usual, the propositions on the agenda were numerous, the diplomatic machine is a complex toy made up of commissions that must bring 82 participating nations together in an unanimity based regime.

Beyond the ordinary administrative details on non-substantial matters, everyone knew that all expectations were converging to a specific point. The core of the debate was – and still is – the issue of the possible extension of the definition of conflict diamonds. In fact, as things have evolved in recent years, the elimination from the market of rough diamonds associated with injustice and illegality seems to be a process based on a leaking pipeline. It is widely agreed on the fact that at the time of extraction the discerning sieve allows injustice and violence against people and the environment to pass through its holes, along with those diamonds that the current system can’t stop.

The core of the requested reform lies precisely in the need to overcome a too narrow twenty years old definition of “conflict diamonds”. This definition just identifies them as those “used by rebel movements or their allies to finance conflict aimed at undermining legitimate governments”. The new millennium proved that this limitation of the KP scope is obsolete. The reduced range of action can be explained by the initial context in which the KP came to life, characterized by local African civil wars in the absence of a recognized and legitimate central governance (see “Box 2 – African civil wars in the 90s. The reasons why the Kimberley Process (KP) was established”). Diamonds funding civil wars were just the tip of a bigger iceberg of weaknesses of the supply chain cluttering the tables at the time of initial negotiations which led too the approval of the original scheme. Having been the KP construction a true challenge for international law specialists it was unlikely that as early as in 2003 the legal spectrum could be wide enough to allow immediate action against all cases of offenses concerning the management of this precious raw material.

The 9/11 shock and the subsequent necessity of a prompt reaction to terrorism, reportedly fueled by illegal sales of gemstones also, contributed to focus on a specific and narrow area of intervention, thus overlooking many kinds of violence and conflicts, such as sexual violence, torture or inhumane treatments perpetrated by governmental armed forces operating against the settled communities in diamond rich territories.

These evident abuses were just hidden by the fact of not being included by definition in the inevitably limited mission of KP. Nonetheless they have been affecting negatively the diamond industry formally satisfied with the fact that the alleged violations were not financing wars against legitimate governments. In other words, as the system still works nowadays, abuses committed by actors other than rebels against the recognized governments are not taken into consideration.

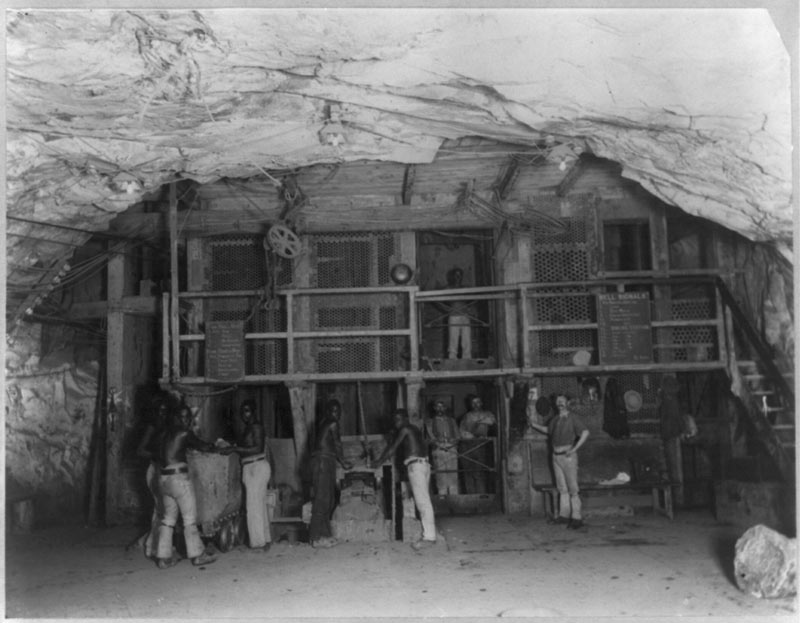

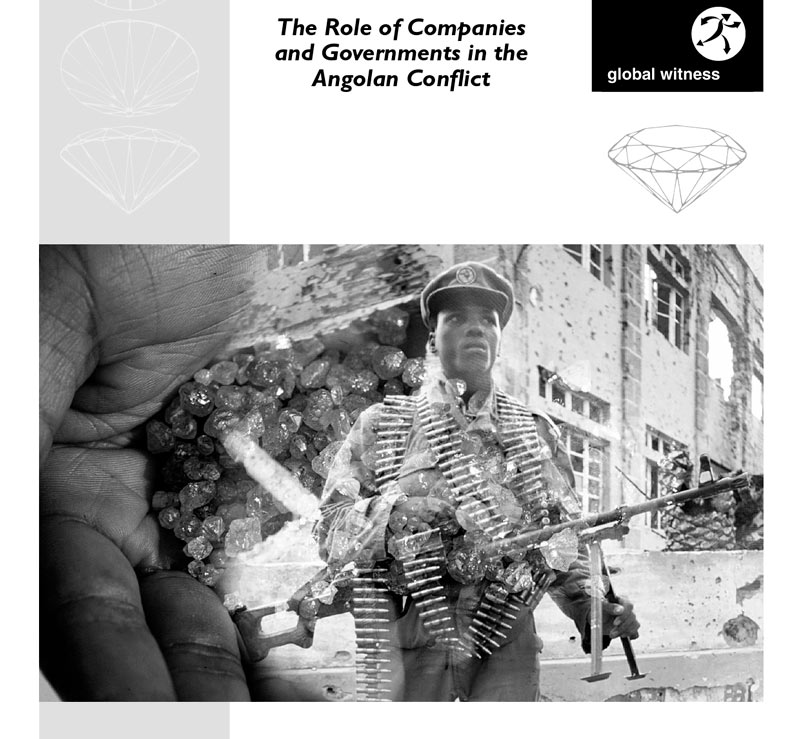

Box 2 – African civil wars in the 90s. The reasons why the Kimberley Process (KP) was established

In the 1990s it became evident that the bloody post colonial civil war in Angola between two major contending groups was fueled by diamond traffickers supporting UNITA’s action against FRELIMO. This drew the attention of the NGO Global Witness that released a report accusing private companies, including De Beers, to make business with what were named “conflict diamonds”. Later evidences were showed about the involvement of other African countries, such as Sierra Leone, DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo), Ivory Coast and Liberia in the trade of rough diamonds financing wars.

Fearing that the NGO campaigns would affect the image of the gem, the diamond industry, under pressure of UN Security Council Resolution urging the use of a certification origin regime woke up at the beginning of the new millennium and established the World Diamond Council in an attempt to implement a first voluntary system of certification, including the “Conflict free” certificate and supporting a government-controlled system over the import and export of diamonds.

Disappointment after expectations. The KP crisis comes from afar, from the tripartite mechanism that highlights conflicting interests

It seemed possible to do something. But what came out of it? “The Kimberley Process (KP) Plenary, under Indian chairmanship in New Delhi, was a sad and surreal spectacle. The 82 participating states lost themselves in excruciating discussions on rules, procedures and trivialities as they could only agree that, in fact, they do not agree on anything substantial”.

This statement is a true admission of the failure of the reforms. These words are particularly important because at the end of 2019 they were not pronounced by a journalist or a commentator but by Shamiso Mtisi, Zimbabwe-based coordinator of the KP’s civil society coalition. It should be remembered that the Kimberley Process is based not only on the member countries respectively implementing their national legislation in accordance to it, but also on two other pillars (see “Box 3 – The “tripartite consensus” or “dynamic consensus”. Industry and NGOs are part of the KPCS”). The first one is the civil society, whose role was reaffirmed in a UN Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 1 March 2019 (Civil Society Coalition) represented by the NGOs. The second leg is the industry, composed by the WDC (World Diamond Council) whose president was as much realistic and admitted that “… the failure of the political process to achieve consensus was a missed opportunity to enhance the effectiveness of this foundation stone of integrity in the diamond business”.

Box 3 – The “tripartite consensus” or “dynamic consensus”. Industry and NGOs are part of the KPCS

The KPCS is technically defined by specialists as a soft law, an international instrument not legally binding such as a treaty, but of general and wide international application. It promulges norms in a Scheme (Guidelines, Principles, Declarations, Codes of Practices, Recommendations and Programs, Decisions are other instruments of the same kind).

The scheme is subsequently implemented and enforced by national laws. Any specific legislation would have required too longtime to be developed in the jurisdictional system of every single participant. Therefore, once the principles are widely agreed upon, disrespecting the KPCS mandates could lead to isolation from the other countries and ultimately to the impossibility to trade even though no formal suspension of any countries is expressly envisaged in the KPCS.

In a framework characterized by voluntary application, decisions are taken by consensus among the participants that must take in due consideration the indications by the NGOs, with no voting rights.

Delhi’s reformist project was a fiasco as all the parties recognized. What is the reason explaining the decisive role of the diamond industry as well as of the representatives of the social parties? Once again we must go back to the climate in which KP came to life in 2003, in the form of little more than a set of guidelines to restore the consumers’ confidence thanks to a certificate of legitimacy.

Diamond consumers were expecting that the supply chain would make clear that they were buying safely thanks to the new Kimberley certificate (see “Box 4 – Year 2000. How Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) took place”). To do this, it was necessary to build the first system, in the history of jewelry, producing a response of responsibility to the market call for ethical practices.

Box 4 – Year 2000. How Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) took place

Neither the trade restrictions based on existing international agreements, nor the single nations using their own legislation were sufficient to find a solution. The only possible way to react against “conflict diamonds” was an international conference promptly organized in Kimberley, South Africa, in 2000, gathering all the stakeholders concerned with challenging the illegal diamonds flood into the market.

Subsequent meetings took place in South Africa, Namibia, Russia, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Angola and Botswana, starting what later was named the Kimberley. Therefore this is not an international treaty but a series of open negotiations to achieve rules to be adopted in the trade. This “Process” was soon recognized by two UN resolutions soliciting the involvement of the widest possible scope of stakeholders of the industry including producers, exporting and importing countries.

The final step of the KP was the Interlaken Declaration of 5 November 2002. 37 participants (currently 54 representing 81 countries, with the European Union counting as a single member) with NGOs Global Witness, Partnership Africa Canada (PAC) and the representative of the industry World Diamond Council as observers gave birth to the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme for rough diamonds. Its purpose was to start monitoring their impact on peace and security and preventing the trading of conflict diamonds in violation of human rights.

Until then, action had been taken in accordance with just national laws and policies. Now, at the beginning of the millennium of globalization, single governments did not have adequate tools to cope with the unprecedented – and to some extent unexpected – need for legitimacy. Interconnected and ethically aware societies such as the modern ones, increasingly concerned with practices of responsibility, are able to measure the ethical commitment as whatever other company performance indicator, a real revolution impacting the business as a whole. A set of new ethical principles, theorized by the economists since the 70s, became a requirement the market by now expects as a standard. The promotion of due diligence practices was more a competitiveness factor than a mere compliance to a new set of rules or an option of good-natured philanthropy.

But for a company establishing correct relations with its employees in New York is one thing, another thing is to prove the integrity and the legitimacy of the questionable path of precious raw material from such an insidious continent like Africa. Furthermore, it should always be remembered that, by definition, CSR compliance can only be achieved by the enterprises in a multisided and equal environment where no one – and governments are no exception – can act by his own. Social responsibility can’t be implemented by governmental decrees. All the main stakeholders – in this case the combined group including industry, institutions and civil society – legitimize the ethical authentication process.

From this point of view, the KP has functioned as a laboratory incubating for the first time jewelry products during their process to attain an ethical status, based precisely on these three pillars. But soon the tripartite construction fell into a crisis. Global Witness, the NGO which acted as the Kimberley certification model inspiring muse, quit the KP in 2011, a move following the controversial readmission of the diamonds from the Marange area in Zimbabwe (see “Box 5 – The withdrawal of Global Witness from the KPCS and the boycott of NGOs of 2011 and 2016 plenary meetings”).

Unquestionably the third sector by its very nature cannot compromise with corporate programs, based solely on the search for revenues and profits. By doing that it would contradict its mission. So during the last decade, CSC group have been increasing its opposition and reinforcing its function as an umbrella organization of the non business components of the Kimberley Process in charge of objecting the deliberations taken by the deciding establishment.

Box 5 – The withdrawal of Global Witness from the KPCS and the boycott of NGOs of 2011 and 2016 plenary meetings

In 2001, two months after the plenary session, boycotted by the Civil Society Coalition group and allowing Zimbabwe to resume exportations, Global Witness left the initiative. This was definitely a grave decision as the one abandoning the project was an influential leader of the civil parties, among those that started the Kimberley Process. In a statement Global Witness explained that “the Kimberley Process’ refusal to evolve and address the clear links between diamonds, violence and tyranny has rendered it increasingly outdated”. This episode marked the beginning of the deterioration of the relationship between the Civil Society Coalition and the Kimberley Process. The remaining NGOs in fact have few resources and little background in conflict diamonds and are less able to efficiently challenge the industry and the members of the Kimberley Process. The dispute on how to deal with the controversial Marange Diamond fields in Zimbabwe undermined the mutual confidence among industry, national states, and civil society.

Again in 2016 the Civil Society Coalition boycotted the proposed Chairmanship of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This opposition, not based on evidences of actual abuses on the ground as in the Marange case, concerned instead the alleged undervaluation of diamonds officially imported by UAE from African countries. According to the Civil Society Coalition’s point of view this represented a bad practice that was reducing the profit of the weak exporters of diamond rough.

There is black hole on the African checkerboard involving private security forces of formally KP compliant countries

Interestingly it was just the various field study missions by NGOs participating in the KP to shed light on the extending black hole made up of all those violent practices not punishable under the narrow range of possible interventions allowed by the current KP regime. Among them the accusations on the abuses in the Marange’s diamond fields have made a resounding echo (see “Box 6 – The Marange case. Zimbabwe puts the KPCS in trouble”).

It should be noted that all these dark areas in which the alleged offenses occur show common characteristics. First of all, the geographical area is the African continent, the place where in the new millennium the race for raw material control is taking place. Many African countries, almost all those rich in diamonds and other gemstones, have no choice but resorting for their economic development to the technological and financial support of technologically advanced and market connected foreign industrial powers once they start negotiating with. Often the exploitation rights of their mineral wealth are conceded in return of investments. Not surprisingly many accidents are provoked by the consequences of the violent repression of intruders into licensed concessions.

The trend line of the accusations shows similarities between the involved countries: the challenged abuses are almost always initially the work of national military forces. Subsequently, the often brutal illegal exercise of force results more and more associated with mining companies’ private security. There is an explanation for this shift of positions among the defendants: the stronger has been the pressure in recent years from the international community to obtain ethical compliance, the more often the direct involvement of the national military force has been replaced by private militias generally recruited as private security forces. A regular army is recognizable and as such its illegal behavior can have consequences under shared international regulations. On the contrary, being scarcely recognizable and scarcely punishable by inefficient or colluded judicial systems, private security deviations do not formally jeopardize the ethical legitimation processes such as the Kimberley certification, which any country cannot formally escape.

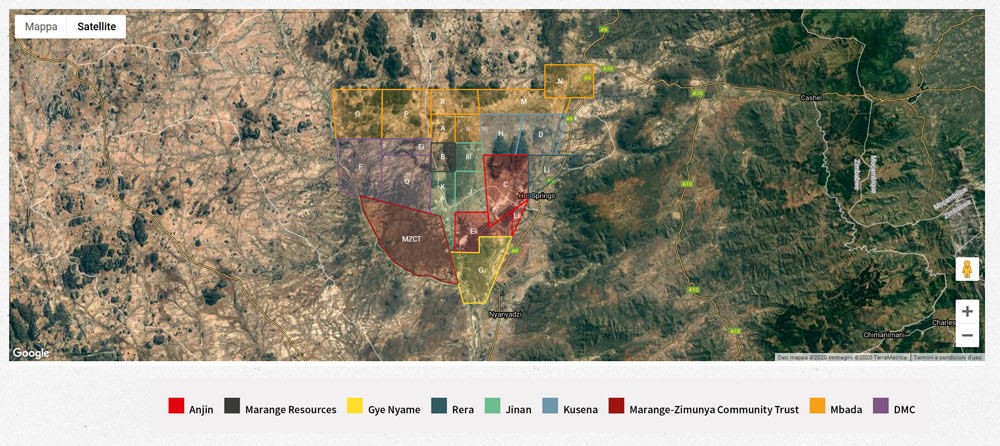

Box 6 – The Marange case. Zimbabwe puts the KPCS in trouble

Marange is an alluvial diamond mining area in eastern Zimbabwe, initially prospected from 1994 to 2006 by De Beers which subsequently sold the rights to African Consolidated Resources (ACR) after the deterioration of the relations with the local leadership. Then the government gained control over the concession area through a subsidiary state-owned company. But in the meanwhile an estimated 35,000 artisanal miners have been flooding to Marange fields initially with little or no opposition by police. The race for diamonds resulted in fights and disorder and army provoked more than 200 casualties among illegal miners. Officers were found involved in corruption, extortion, rapes, tortures, beatings, forced labour and smuggling towards neighboring Mozambique.

In 2009 a review visit to Marange sent by the KP, under request of proper investigations raised by the civil society, reported the non-compliance of Zimbabwe with the KP minimum requirements. In November 2009 the KP agreed on a joint work plan under which the Zimbabwean government was asked to take action on legalization of small scale mining, fighting against smuggling and providing it safety in the Marange area. In the meantime Marange diamonds were banned as a result of non-compliance to KP exportation administrative requirements. If the administrative inadequateness was the reason behind the ban it must be noted then that the violation of human rights by itself (not included in the KP actionable offenses) was not a sufficient reason to place a stop to the export.

So in 2011 the chair of KP, at that time DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo), lifted the ban and made the alluvial diamonds of Marange again available on the international market. This not unanimous decision was very controversial because just two sites, to of many, were found to be compliant to the KPCS standards. Therefore not all diamonds from the Marange mines could be certified and there was no certainty that the stones from adjacent ineligible areas were properly separated before entering the market. The lift of the ban was openly disapproved by EU, USA, many NGOs and by the Rapaport group, which called for a ban in its trading platforms.

The list of unpunished violations, the sword of Damocles against Kimberley’s legitimacy

Repeated episodes are under the spotlight of international observers, concerning abuses perpetrated by the private security force against miners in Zimbabwe’s Marange area, where victims were desperately searching employment in the crisis-stricken country (see “Box 6 – The Marange case. Zimbabwe puts the KPCS in trouble”). Poverty still affects Zimbabwe despite the fact that the country has exported 2.5 million carats of KP certified US $ 170 million in 2017. Local sources estimate at least 40 artisanal miners dead annually and cite instances of some having their hands tied behind their backs whilst dogs are set on them. In spite of human rights training services available for the security agents of ZCDC (Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company) as well as two diamond security conferences held in between 2018 and early 2019, attacks on miners in Zimbabwe have continued to raise concern.

Angola shows similar conditions of alleged violence in the diamond mining areas. Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan renowned human rights advocate and investigative journalist, since 2008 director of the anti-corruption organization Maka Angola, reported about this in 2015 in the investigation book “Blood Diamonds: Corruption and Torture in Angola”. He describes the human rights abuses and violations committed by security guards and soldiers in the area of Lunda and Cubango where the diamond fields are located. Marques de Morais reveals that at least seven generals co-owners of a private security company were criminally responsible for abuses against miners. In the first pages Marques De Morais explicitly claims that “by any objective definition, diamonds mined in these areas are blood diamonds, and to trade with the Angolan diamond industry is indisputably to trade in blood diamonds. After years of ignoring the problem, the international community should acknowledge this fact and take action”.

At the time of its release, the well documented book, now available online, raised international concern in the international press. Yet this didn’t prevent Angolan authorities from giving the journalist, already previously arrested after reporting on corruption and describing president dos Santos as a dictator, a six-month suspended jail term for defaming army generals. Significantly Dos Santos’ case, although he has been honored by the International Press Institute (IPI) as 70th World Press Freedom Hero, did not resound noticeably in the KP reforming debate.

In Tanzania the large-scale Williamson diamond mine, located in Mwadui, Shinyanga region and run by the London listed company Petra Diamonds, which took over De Beers in 2009, is also reported to be subject to intrusion from local people entering illegally the company’s licensed area to sustain their poor livelihoods. In the area private security contractors have allegedly perpetrated killings and assaults on these intruders while deaths, injuries, disappearances, detentions are reported since a long time.

A Parliamentary probe into the diamond mining sector reported gross irregularities around Petra Diamonds’ contract, license and diamond valuation. A 71,000 carats consignment of Petra’s diamonds on the way to Belgium was confiscated at Dar Es-Salam airport in 2017 under allegations of underreporting their value.

Another open chapter concerns the environmental damage affecting the inhabitants of the territories surrounding the diamond fields. These disadvantages also are not covered by the KP list of punishable inconveniences supposed to bear a bad reputation to the diamond industry.

For example, water contamination from Gem Diamonds’ Letseng Diamond Mine in Lesotho supposedly is causing serious harm to local wetlands where farmers are depending on agriculture and livestock rearing. So they are forced to compete with one another for clean water, an increasingly scarce resource after possible contamination from the mine.

In Sierra Leone, communities, protesting since 2007, are affected by contamination of air and well water, destruction of livelihoods, crops and homes allegedly resulting from large-scale mining activities carried out by diamond miner Koidu Ltd. Four individuals protesting for better safety conditions for their communities were killed by police during demonstrations. Redresses for these families have been asked but legal procedures will take time and compensation is far to be achieved.

The borderline case of the Central African Republic will mark the future of KP

A long list of African countries governed by authoritarian leaderships and affected by corruption presents political and economic conditions that might result in a potential threat to the KP. The Central African Republic shares many aspects with other African countries, all of them coming from a colonial past and all of them run by national elites associated with the military force and frequently opposing each other. Often the leaders are former Army officials emerging from a fragmented texture made of a variety of ethnical tribal groups. For example, Angola, Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone, Congo, fall in this category. All of them are diamond-producing countries currently admitted to the scheme, but they would highlight severe violations in case the process would be reformed.

By far the most paradigmatic case is the Central African Republic (CAR), the only nation where a part of diamonds, after a three year ban partially ended in 2016, currently fall under the KP’s definition and cannot be exported (see “Box 7 – The Central African Republic, diamonds from an out of control country”). In this regard CAR’s history is not an exception to the standard post colonial path characterized by specialized strategies for raw material exploitation put in place in backwarded and disadvantaged countries unattractive for western investments in fields other than mining.

These investments in the energy, military and infrastructure fields are now being developed by the Russian Federation which started taking position in Central Africa at the time of the establishment of the United Nations peace keeping mission. Later mercenary forces have been deployed under control of Yevgeny Prigozhin, a controversial figure openly associated to President Putin. Russia is pursuing a policy of military and economic penetration into the entire continent in contrast to China and to the detriment of France and other western countries. But what is at stake in the country is the raw materials, mainly uranium and diamonds which Russia aims to control through agreements made with both the government and the rebels. It is a strategy based on territorial fragmentation, a balancing act between legitimate and illegal entities with the purpose of pacifying the country the minimum necessary to safeguard and protect the mining companies, allowing exportation and supporting their own allied groups.

Currently diamond exports are permitted in CAR from a number of compliant KP monitoring zones only. Russia, new Chair of KP in 2020 is officially asking to lift the ban. Deputy finance minister Alexei Moiseev said on February 25, 2020 that restrictions are resulting only in increasing smuggled diamonds. This proposal openly conflicts with what the U.S. Department of State declares in November 2019: “Due to lack of government control and widespread rebel activity in the east, KP-compliant exports from eastern CAR are not possible”. This arm wrestling fight will decide the future of Kimberley.

More than an incentive to the mining process legitimacy, more than a warranty against the terrible conditions of people suffering abuses for the control of the diamond territories, the Kimberley process for the Central African Republic becomes the battle ground between opposing interests. Actors change, France is no longer here, China is still far being involved in other African countries, but the game remains the same, if not even more exasperated. So far KP historically has been available to formally pacified countries in presence of a recognized central government apt to implement its rules. The Russian proposal, when accepted, would represent a serious injury to the KP credibility, because granting certificates in not pacified areas would legitimate national desegregation into a new normalized mosaic made of diamond rich areas under rebels control and territories under formal governmental control, both under Russian direction.

Box 7 – The Central African Republic, diamonds from an out of control country

The last years have been characterized by increasing violences caused by many parties including the predominantly Muslim Seleka faction and the Christian and Animist self-defence groups known locally as the “anti-balaka” or “anti-machete”. Grave human rights violations are wide spread across the country. Neither the deployment of a UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSCA) in 2014 to protect civilians nor the election of Faustin-Archange Touadéra as President in 2016 were sufficient to restore peace.

The country is experiencing a devastating fight between government and rebel groups resulting in more than 1.1 million displaced people (nearly 20% of its population) with many casualties. In March 2013 in fact a coalition of rebel groups, known as the “Seleka”, seized CAR’s capital, Bangui, violently ousting the President François Bozizé putting their leader, Michel Djotodia, in his place.

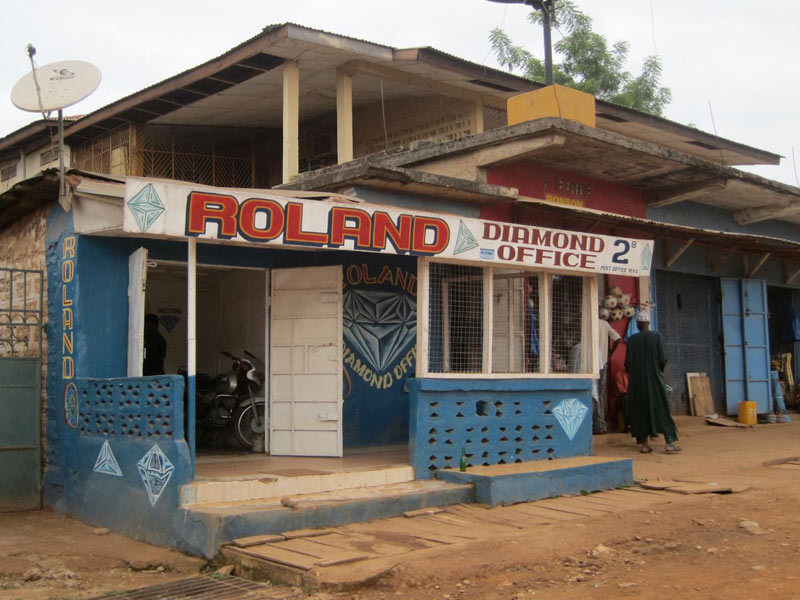

The transition between the French domination and the establishment of an independent government was essentially based on the control of diamond deposits, the most important economic resource (39 million carats of exploitable alluvial diamonds according to United States Geological Survey). These reserves, exploited almost exclusively by way of informal artisanal and small-scale mining, are concentrated in two main river systems (in the southwest, around the Mambere and Lobaye rivers and in the East, around the Kotto River).

The diamond sector was nationalized in the 60s in accordance to what many other African countries did and managed in turn by national leaders through a very opaque governance marked by widespread corruption.

The diamond market will pay a price to the virus. If the KP ends it will happen that…

The consequences of COVID-19 have overwhelmingly taken over from the geopolitical situation that has been recalled. From 2020, diamonds will experience a phase of turbulence, a fall in purchasing power and an inevitable downsizing of the ethical appeal of the product. The KP, like any social responsibility initiative, is all the more incisive the more stable the market is. After the Delhi misstep, a United Nations Assembly held on March 3, 2020 released a resolution attempting to recreate consensus on the reforms. We will see. At the moment, however, the COVID-19 earthquake has suddenly canceled the urgency of the issue of the rejected KP changes. How will the contrast between those in favour and against the widening of the range of currently actionable violations evolve?

A strong confrontation divides the involved parties, affecting and modifying their behavior. In fact, the large-sized and highly capitalized multinational mining companies exploiting the underground deep diamond deposits detain huge financial resources (about 75% of the mined diamonds value is made up of vertically integrated producers). Using their strength they can support the territory where the operations are carried on in force of solid agreements with local governments. So they have the means to apply diligent practices and prove to the industry that they actually act responsibly. Being De Beers, Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton, Alrosa big and CSR skilled miners, a sophisticated ethical message can be conveyed to ensure transparent raw material traceability up to end consumers.

The position of Angola, Congo (DRC), Central African Republic CAR), Ivory Coast, Guinea, Ghana, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Togo, countries with alluvial diamond deposits scattered over wide territories is more fragile (14% of world production occupying 1.3 million people). Diamonds are collected by small or very small artisanal miners and pass through many hands up to brokers. In such situations of instability any ethical authentication process is difficult, though international programs such as the Diamond Development Initiative (DDI), are helping (see “Box 8 – Before Kimberley it didn’t matter where the diamonds came from”). Small and medium-sized companies don’t have a stricter KP certificate at the top of their priorities. In fact, for countries with poor ethical accountability, the risk of an embargo is greater the more the KP successfully achieves a wider mandate to fight local abuses against communities and environment.

NGOs also had to change their attitude. Once the public opinion starts feeling that the mandate may have been betrayed for opportunism purposes, the easy relation with the industry and the governments, like it was at the initial stage of the KP, would prove to be too acquiescent becoming a deadly embrace. If the mechanism turns to be deliberately short-sighted towards evident and not prosecuted violations ONGs have little choice but opposition. The lesson has been learned, the very NGOs identity is based on the duty of a strict supervision.

Box 8 – Before Kimberley it didn’t matter where the diamonds came from

For many decades, the gem and jewelry industry failed to take in due consideration the issues on where and how legally diamonds were sourced. Traditionally the diamond trade was not based on a simple vertical chain tracing the exchanges from miners to the wide distribution.

Consumers knew little about their origin, while several layers of middlemen used to control the trade by uncountable transactions occasionally through adjacent countries. This system ended up bringing into the market undifferentiated lots, including diamonds of alluvial origin coming possibly from military warlords of turbulent African countries, mixed up to those produced by large scale and accountable mining companies.

The cutting industry is aware of the importance of responsible sourcing but has never had a great interest in having more selective and stricter sourcing processes resulting in additional restrictions on access to rough diamonds. Nowadays the industry must take note that new ethical, alternative or supplementary authentication processes other than Kimberley certificates are available, such as the Blockchains, the supply chain digital tracing registers that can validate all the passages up to finished jewelry.

Day by day the Blockchains are becoming the most powerful competitors of the KP being able to integrate rough diamonds sourcing with a significant amount of additional information concerning not only responsible sourcing but also ethically compliance of manufacture. Additionally technical and aesthetic information of any finished diamond placed on the market can be offered. To the big international jewelry brands KP certification is only a part of broader and more sophisticated ethical protocols.

If the KP decays further, even that part would no longer be necessary, because the big players like De Beers and Alrosa are already starting to take action to activate a common blockchain, Tracr, to take action activating a common blockchain and track the entire supply chain starting from mining. This would please the trade and could be the coup de grace to the old dear KP certificate.

The decline of the KP, according to some observers, could also direct some groups of consumers towards synthetic diamonds which not surprisingly are marketed as more ethical or having ethical credentials easily available. The future of diamond legitimacy certification can be read focusing on the historical transition of the KP. In 2003, when the mechanism was launched, Kimberley more than a simple certification system was a kind of symbol of a common commitment, a concept of a new order based on the respect for the rules. The rules were the result of an agreement between independent states sharing general values and a consequent collaboration project. In 2020, the need for compliance is instead a competitive activity concerning individual companies rather than international treaties and the market rather than agents pretending to regulate it. In the new context, the post COVID-19 diamond industry could either reduce its CSR commitment or focus on more hasty solutions.

As a matter of fact it is traceability, intended as geographical origin, what the diamond industry has been asking for some time now. This is how new value will new added affecting the future demand. Nowadays what the diamond industry for some time now really wants is the traceability, intended as geographical origin, considered as the true value adding driver, the one that will influence the future demand. More advanced and conflict-free countries like Canada or Botswana, for example, can emerge just because the geographical origin works as a brand echoing responsibility compliance. The huge gem and jewellery companies have learned that they can start making on their own, using the KP without depending on it. Last but not least, the adoption of a strong national legislation such as the Dodd-Frank Act in the United States implies that any single company assumes its own direct ethical responsibility without transferring this issue to international organizations (see “Box 9 – The Dodd-Frank Act and other regulations on conflict minerals”).

And this being the case, paradoxically, a KP that would want to inspire more sanctioning powers to its members, while deciding more sales bans and extending the list of obligations, would put in trouble precisely those countries that should instead be pushed towards a greater transparency and fairness. Therefore a seventh of the world diamond producing countries might find more convenient abandoning the ethical issues and enter the market through the open doors of those companies impervious to due diligence and sensitive only to price dumping.

Box 9 – The Dodd-Frank Act and other regulations on conflict minerals

The Kimberley Process had the merit of encouraging institutions and international organizations to make a stronger effort to tackle the use of all other minerals used to finance armed groups. But it is not the only intervention on the matter. As early as in 1999 the United Nations had already launched the Global Compact, a non-binding pact to promote businesses worldwide in a way to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies expressed in 10 principles related to human rights, contrast to corruption, environmental protection. The OECD Guidelines as well provide non-binding principles and standards for responsible business conduct in accordance with applicable laws and internationally recognized standards.

The most important legislation impacting conflict raw material is the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, a U.S. Federal Law, passed by the Obama administration in 2010 to prevent armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and surrounding regions from taking advantages from marketing minerals such as cassiterite (for tin), wolframite (for tungsten), coltan (for tantalum), and gold ore, used in the manufacture of several devices, including consumer electronics such as laptops and mobile phones.

The Dodd-Frank includes in its definition of conflict minerals “any other mineral or its derivatives determined by the Secretary of State to be financing conflict in the [DRC] or an adjoining country”. Diamonds can be included in the list. Under the Dodd-Frank Act public companies in the U.S. must disclose their use of such materials in their products and are given the new duty to determine if they are sourced in an ethical manner.

Further readings:

- Arribas G.F. (2014) “The European Union and the Kimberley Process”, retrieved from https://www.asser.nl/media/1645/cleer14-3_web.pdf

- Bieri, F. (2010). “From blood diamonds to the Kimberley Process: how NGOs cleaned up the global diamond industry.” Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Collier, P., & Hoeffler, A. (1998). “On economic causes of civil war.” Oxford Economic Papers, 50(4), 563-573.

- Dussenne A. (2014) “To what extent can NGOs still play a role in the Kimberley Process?”, retrieved from https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/33826166/DUSSENNE-DOCUMENT-2017.pdf?sequence=1

- Hughes, T. (2010). “Conflict Diamonds and the Kimberley Process: Mission Accomplished or Mission Impossible?” South African Journal of International Affairs, 13(2), 115-130. Cullen, H. (2013). Is there a future for the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme for conflict diamonds? Macquarie Law Journal, 12, 61-79

- HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH (2009). “Diamond in the rough. Human Rights abuses in the Marange Diamond Fields”, retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/06/26/diamonds-rough/human-rights-abuses-marange-diamond-fields-zimbabwe

- IPIS (2019). “Dissecting the social license to operate: Local community perceptions of industrial mining in northwest Tanzania”, retrieved from https://ipisresearch.be/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1908-DGD-TZ-LSM_web3.pdf

- KCSS (2019). “Real care is rare”, retrieved from https://www.kpcivilsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Report-real-care-is-rare-FINAL-web.pdf

- Kurecic P. , Hunjet A., Perec I. (2014).”Effects of dependance on export of natural resources: common features and regional differences between highly dependent states” Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Petar_Kurecic/publication/272818893_EFFECTS_OF_DEPENDENCE_ON_EXPORTS_OF_NATURAL_RESOURCES_COMMON_FEATURES_AND_REGIONAL_DIFFERENCES_BETWEEN_HIGHLY_DEPENDENT_STATES/links/54ef873a0cf2432ba656e59e/

- Le Billon, P. (2001). “The political ecology of war: natural resources and armed conflicts.” Political Geography, 20, 561-584.

- Ross, M. (2003). Natural Resources and Civil War: An Overview.

- Vircoulon, T. (2010). “Time to rethink the Kimberley Process: The Zimbabwe case. Global Policy Forum”. Retrieved from https://www.globalpolicy.org/the-dark-side-of-natural-resources-st/diamonds-in-conflict/kimberley-process/49573-time-to-rethink-the-kimberly-process-the-zimbabwe-case.html

Article by Paolo Minieri, published on IGR – Italian Gemological Review #9, Spring 2020